Tash was awakened by the silence. For a very long time he had lain there listening to the shuffling and wheezing and jangling and occasional unhappy gabbling of the other sacrifices, and he must finally have fallen asleep, but he awoke with a start to a silence like death. No one stirred. No one wheezed or muttered nonsense words to themselves. It was yet harder to see than it had been, for some kind of thick fog had filled the chamber and the lights on the pillars spent themselves in muddled grey-green blobs and failed to illuminate anything more than a few paces distant.

‘I hope they are not all dead,’ said Tash. It would not really have been any worse for him to be chained up with some hundreds of dead bodies than with some hundreds of sacrifices who were to be killed in a few days at any rate, but it was a horrible thing to imagine, and frightened him every bit as much as it would you or me. He felt at the idiot boys chained to his left and to his right, but could not wake them, nor could he tell for sure whether they were breathing or not. When he moved, his chains clanked, but less than they should have, like they were clanking underwater.

‘I wish I was anywhere else at all,’ thought Tash unhappily.

A moment later things became yet more alarming, for Tash felt something crawling on his arm. It was a quick tickly rasping thing with too many legs, as big as his hand, and he could see it only as the merest flicker of movement in the gloom.

‘I must be still and quiet and maybe it will not bite me,’ said Tash to himself. He had learned this way of dealing with biting creatures through painful experience. So he sat very still as the something crawled down to his wrist and sat there in an unruly ticklish way like a newborn sister, and as another something of the same sort crawled onto one of his legs and scrabbled to his ankle, and then another, and another, until the rasping things were perched everywhere the chains bound Tash to the stone post. Then they began to gnaw. Not on Tash – for which he was very grateful – but on the fetters that held him. He could feel the patient grinding of their teeth in his bones, an inexorable gnawing that went on and on without ever slowing down or speeding up. He had the feeling that if these creatures with too many legs set their tiny minds to it they would simply keep gnawing forever through anything that was in their way, flesh and bone and metal and stone, year after year and generation after generation, until they had gnawed a tunnel through the world from one side to another.

After a long time the things with too many legs had chewed through all of Tash’s fetters. The chains fell dully to the floor, one by one, and the many-legged things gathered in a vague mass before him. He could see their green eyes shining now, little pinpricks of light in the fog. They were looking at him.

‘It is better to do something than nothing,’ thought Tash, which was one of the proverbs he had heard all his life whenever he had been found doing nothing. He stood up, which was more difficult than he expected. First one of the many-legged creatures darted away into the darkness, then another one. The remaining green eyes watching him seemed to be brighter. He took a step in the direction the creatures seemed to be going and they took off before him in a rush, their eyes bounding like grith nodules in a pot of boiling water.

As Tash walked away from the pillars where the sacrifices were chained, the fog lifted and the eyes of the creatures grew brighter and brighter. The strange silence also faded, and Tash could hear the scrape of his own feet on the pavement, and the rustle of the many-legged creatures around him. There were more of them than there had been: more and more, until he could dimly see his injured hand by the glow of their eyes, and the shadows cast by their capering bodies. They were leading him away from the doors to the outside, across the vast chamber, deeper and deeper into the evil-smelling darkness.

‘Now I am somewhere else, as I wished,’ thought Tash. ‘It is better, I suppose. How this chamber goes on and on. ’

If it had been outside and lit, it would doubtless have seemed no great expanse, smaller than many of the grith fields in which Tash had spent his life; but it was inside and dark, so seemed to be without beginning or end.

But at last it did end: stone walls closed in around Tash, and the air grew damper and less evil-smelling. The creatures danced around him, steering him first one way and then another through what seemed to be a maze of passages, sometimes down, sometimes up, but more often down. The air grew damper yet, and the walls Tash came close to were slick with slime. Once they passed over a thunderous stream of water, and another time Tash had to climb over a statue that had fallen over to block the way. Tash would have liked to stop and examine the statue more closely, for he had never been so close to any of the great carven images which the Tower was decorated, but the many-legged creatures became so terribly agitated when he bent down to peer at it that he judged it unwise.

‘After all if I scare them away I will have no light at all, and will never be able to find my way anywhere in the dark,’ he thought. And he followed the creatures on, and on, and on, through the maze.

Tash was dizzy from watching the green eyes of the creatures, and weary from not being able to stop and ponder things, and feeling rather sore from one particular place he had been clouted that had not seemed such a big deal at the time, when the passage he was following ended abruptly in a wall.

Several of the creatures took off excitedly into the darkness, while others scrabbled up the walls and even clung to the ceiling above Tash’s head. Before he had time to think of much of anything at all he saw a light that was not dancing and green. It was a bluish light like fire that was very bright – really too bright to look at directly – and it traced a line along the wall in front of him, from the floor to somewhere well above his head. Then it grew wider and wider, and was a door opening into a room, where everything was too bright to see. Of course the light poured out of this room as well, so it was just as impossible to see anything outside, but Tash was vaguely aware of the many-legged creatures capering into the room like mad things. A slightly darker patch loomed out of the brightness, took Tash by an arm and steered him into the room, less roughly than he was accustomed to.

‘Stand still,’ said a voice. ‘Don’t fall over. And straighten up.’ It was the voice of a very old thalarka, and it spoke the words very carefully, as if they were made out of something fragile and would break if spoken too roughly.

Tash did his best to follow these sensible instructions. Little by little his eyes adjusted and he could make out the source of the voice. The unbearable brightness came after all from a rather small lamp, which filled the room with wavering blue light and a sickly sweet smell. The lamp hung from the ceiling above a stone table covered with mysterious devices, which under normal circumstances Tash would have been inordinately curious about. There were books, too, like the ones the tax collectors carried, but instead of one there were scores, stacked on the table and on shelves on the far wall. Clinging to the walls – and the shelves – were very many of the things with too many legs, shifting ceaselessly about and rustling like a crowd of villagers on a festival day. In some curious way Tash was quite sure that they were paying attention to the old thalarka; that he was their Overlord, and that their mindless whispering meant something very like ‘sweeter than narbul venom is it to serve the Overlord’. In the lamplight the eyes that had lit Tash’s way were nearly invisible, buried deep in their wrinkled beastly faces, and they looked every bit as horrid as Tash had first imagined in the darkness.

The thalarka had one withered arm and one blind eye, and stood hunched over so that this eye was level with Tash’s eyes though if he had stood straight he would have been rather tall. He wore a necklace with a sigil of reddish-black stones, and with his remaining good eye he studied Tash with a furious silent intensity.

‘Yes… yes,’ the old thalarka said to himself. ‘You will do.’

It was better to be told that he would do, than to be told he was perfectly and completely useless, Tash thought. He bowed his head and let his arms droop, but he let his arms droop less than he usually did when his elders spoke to him, and when he bowed his head he kept one eye peeking at what the old thalarka was doing.

‘You don’t appear to be witless,’ said the old thalarka, keeping his eye on Tash while picking up a complicated metal instrument from the table. The lamplight reflected prettily from it. ‘Can you talk?’

‘Yes, Much-Knowing and Venerable Antiquated One,’ said Tash. ‘What does that thing do?’

The old thalarka raised the instrument to his eye and looked through it at Tash, making a clicking noise in his throat. He adjusted a knob on its side, took it down and adjusted another knob, then raised it to his eye again. Tash watched these proceedings with fascination. He had not really expected the old thalarka to answer his question, but after making a few more adjustments he said something that must have been an answer.

‘It uses certain little known properties of solar radiation to estimate the eckward component of the aetheric vibrations.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Tash. ‘Much-Knowing and Venerable Antiquated One,’ he added hastily after a moment.

‘Of course you don’t,’ said the old thalarka. ‘If you did, you wouldn’t be chained up under the Procurator’s tower waiting to be sacrificed. You would be the apprentice of one of my rivals, and I would have brought you here to persuade you betray them. Or perhaps to torture you to death, as a warning to your master not to interfere with my plans.’

‘I see,’ said Tash. ‘Much-Knowing and Venerable Antiquated One.’

‘Don’t look so alarmed,’ said the old thalarka, setting down the instrument and picking up another one – still keeping his one eye fixed on Tash. ‘I have no interest in torturing you to death. It is quite clear that you are an ignorant peasant.’ This new instrument seemed to contain some kind of liquid, which could be ejected in a very thin stream through a small tube when the old thalarka pressed a lever. He did this once, spraying a little of the liquid into the air, and the many-legged creatures seemed to find it of great interest. They began to seethe more rapidly, and a few dropped from the walls to scuttle across the floor.

‘What is that?’ asked Tash, forgetting to add ‘Much-Knowing and Venerable Antiquated One’.

‘Aetheric essence,’ said the old thalarka. Slowly and carefully, he traced a circle with the oil on the floor between himself and Tash about a body-length across. The things with too many legs dropped to the floor in numbers and began to cluster along the circle, climbing on top of each other in their eagerness to be close to it. Tash could hear the grinding sound of their teeth in his bones. It was a very unpleasant sound. It began to smell oddly, like the taste Tash got in his mouth sometimes when he had been clouted over the head.

‘What are they?’ asked Tash.

‘Gnawers,’ said the old thalarka.

‘I have never seen them before,’ said Tash.

‘They are forbidden,’ the old thalarka replied. For the first time, he took his eye of off Tash, to do something fiddly with one of the most complicated looking devices while he consulted one of the books on his table. ‘The penalty for keeping them is death by fire.’

‘Aren’t you afraid I’m going to tell on you? No, you’re not. Oh.’ For the first time Tash considered that there might possibly be worse things than being sacrificed to the glory of the Overlord. The odd smell was stronger now, and the sound of the gnawers gnawing, without becoming any louder, grated more and more insistently on Tash’s mind so that he found it hard to think of anything else. He glanced at the door, considering and then instantly dismissing dashing to it and running off in the dark.

‘What do they gnaw?’ asked Tash after a pause.

‘Everything. Plants. Stones. Men. Even – if encouraged properly – the very tissue of space and time.’ The old thalarka carefully adjusted a knob on the device, glancing every now and again to the book. It was open to a picture, rather than rows of ideographs, Tash saw – some kind of tangle of circles within circles within circles that he wished he could look at more closely.

‘Is that what they’re doing?” asked Tash. ‘Much-knowing…’

‘Oh, you are too clever by half,’ said the old thalarka, amused. ‘Of course. Of course that is what they are doing.’ All the gnawers had clustered in a thick writhing mass around the circle of oil that the old thalarka had made, crawling over one another and sometimes biting through each other’s legs by mistake. The air above them was starting to waver, like the air above the smokeless fires that were kindled in the temples.

Tash asked the question then that had first popped into his mind when he had been brought into the room, but kept being pushed back when he thought of other questions. ‘What are you going to do to me?’

‘Don’t you worry about that,’ said the old thalarka. ‘It will be much more interesting than being sacrificed. Hold out your hands.’

‘Why?’ asked Tash. But he held out his hands, being accustomed to obeying orders. The old thalarka picked a length of silvery cord up from the table and tossed one end across to Tash.

‘You don’t want to let go of that. Just keep holding on, and everything will be fine.’ The old thalarka’s one eye glistened with excitement. He had kept hold of the other end of the cord, which now passed directly over the circle of gnawers.

Tash held the end of the cord tightly. It was comforting, despite everything that had been happened, to be told that everything would be fine if he just held on to it. ‘What does it do?’ he asked.

The old thalarka did not answer, but shifted from one foot to another in his enthusiasm, alternately gazing proudly at the seething gnawers and examining a dial on one of his devices. And a moment later Tash had forgotten that he had asked any such thing.

It was very like when the door had opened. There was a crack of bright light, but it was a crack in the air above the gnawers, rather than a crack in the wall. It swiftly got wider and brighter, and then everything inside it fell out of the world. That was the only way Tash could ever explain it afterwards. A little piece of the universe had been gnawed away at the edges, and it had fallen off into something else. The gnawers stopped gnawing; most of them scuttled backwards, while a few slipped over the edge of the void and were instantly whisked away.

Tash’s eyes refused to tell him what was going on in the space above the circle. It was black and piercingly white at the same time, and it seemed to be in ceaseless motion, but not in any direction that Tash had ever encountered before. The silver cord he held disappeared into one side of it, swaying gently, and reappeared on the other. At the edge of the void the air was shimmering, and seemed to be rushing swiftly like water in a millrace; but the space itself he could not manage to get his thoughts around.

‘Magnificent,’ exclaimed the old thalarka. ‘Exceptional. Look at how smooth the interface is! How stable the aetheric flux! If only Zmaar could see me now. If Tzorch knew how much I have surpassed him. The old fool!‘

The whole thing was so fascinating that Tash forgot to be terrified, and stopped attending to what the old thalarka was saying. He tugged at the cord, ever so gently, to see what would happen. Nothing did. It was as if the void was an immovable object. He stared into the absence of universe, willing himself to make some sense of it. The old thalarka was quite right: whatever else this was, it was certainly more interesting than being sacrificed.

‘Is that clear?’ asked the old thalarka sharply.

‘Yes,’ said Tash without conviction, having no idea what the old thalarka had just said.

‘I am sure the powers – inscrutable as They are – will find you an equitable exchange,’ said the old thalarka, his eyes glistening with triumph. ‘Do not let go of the cord.’

‘Y-‘ Tash began. The old thalarka gave his cord the tiniest of tugs, and Tash’s cord was pulled into the void with inexorable force, as if it was attached to a cart that had fallen over the edge of a cliff. Inwards, upwards, and otherwards, Tash was instantly and irresistibly dragged into a place where nothing made sense.

With Reallusion’s recent update to IClone to version 5.5, new functionality has been added in the ability to edit Terrain directly within the program. Reallusion suggests that if you wish to create entirely new terrain, you should purchase Earth Sculptor, their add-in terrain creator, to adjust the material masks for any changes you make. If, however, you don’t possess Earth Sculptor, it is still easy to create material masks for simple terrain projects.

This tutorial assumes a basic familiarity with both Photoshop and IClone. There are plenty of fine tutorials available demonstrating the use of each.

For this example, we will create a simple terrain with some rocky pinnacles in a desert landscape.

1. Setting up your Photoshop document

Load a terrain map in IClone, go to the Terrain tab, and export the height map to Photoshop. I chose the Butte terrain. The image you export will contain a greyscale height map of the terrain, but we are not interested in this. Exporting the file this way simply gives you the appropriate file type and size for the project.

Create five layers above the height map. I named them as follows: Background, Height, Green, Red and Blue. Once you have your new layers, you can delete the original height map, or keep it as a reference if you choose.

Fill the Background layer entirely with black (0,0,0). This layer will represent the lowest parts of your terrain for the height map, and the fourth material type in your material mask map.

2. Creating and exporting the height map.

The height map is simply a greyscale representation of height, rather like a contour map. The brightest, whitest parts of the map are the highest parts of the image, and the darkest parts are the lowest.

For this example, the flat desert plain is the lowest part of my terrain, so all I need to do is draw in my rocky pinnacles as highlights. (If you were drawing a more varied landscape, you might want to start with a dark grey background instead of black, and add shadows and highlights to create your terrain).

To draw the pinnacles, select the Height layer, set the foreground colour to white, and take a photoshop brush with soft edges and a size of about 100 pixels, and draw some white blobs where you want the pinnacles to be. The final result should look something like this:

For a more gradual terrain, you might use a brush with softer edges, decrease the opacity value of your brush, or adjust the brightness of the image. You could choose to paint in grey instead of bright white. You might paint on layers so you could adjust the opacity of each independently. The height and smoothness of the height map is also adjustable in IClone once it has been imported.

Since the pinnacles should be relatively steep-sided, the rapid change from low to high (black to white) is quite suitable.

I took a large soft-edged eraser, of about 50 pixels and an opacity of 25%, and used it to adjust the pinnacles, as below, in order to make them a little more interesting:

Now is a good time to save your Photoshop document. You should also export the Height Map, by selecting “Save As” from the File menu, and selecting .png as the file type.

If you go into IClone and load a terrain into your project, you can double click on the height map in the Terrain settings, and load in a new map. Select the height map file you just created, load it in, and you will instantly see the basic shape of your pinnacles. Here is mine with the Butte material map texturing it.

3. Creating the material mask map

This is the part that Reallusion would like you to purchase Earth Sculptor to do. I have never tried Earth Sculptor. It does look like a convenient tool, with a “what you see is what you get” style interface that allows you to paint textures directly on the terrain. Using Photoshop requires a degree of back-and-forthing, but seems reasonable for simple projects such as this one.

To achieve a material mask with Photoshop, we will colour in the areas that correspond to four different materials that will be present in the final terrain. It is possible to set what these materials are within IClone later. For this part of the exercise you only have to consider which parts of your scene will use different materials.

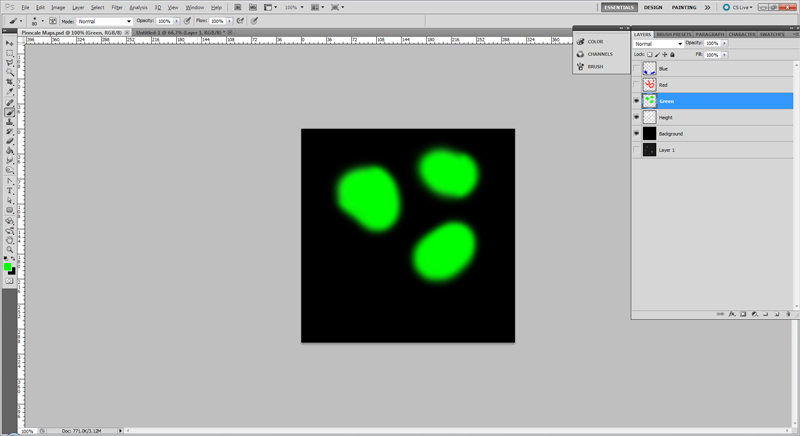

Green layer:

Lets start with the green layer. We will use it for the rock face material for the pinnacles themselves. Select the Green layer, and choose a large soft-edged brush (the same one you used to draw the pinnacles is fine). Use a pure green colour with the RGB value of (0, 255, 0).

Now, simply colour in solid green blobs covering the pinnacles on the height map you drew before. The result should look something like this:

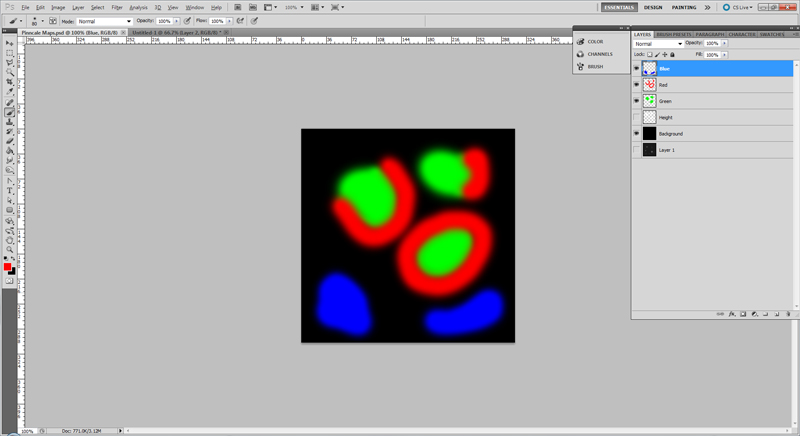

Red layer:

Now for the red layer. This is going to be the stony ground immediately around the base of the pinnacles. Select the Red layer. Take a slightly smaller soft edged brush, set the foreground colour to Red (255,0,0) and draw some rings or semi-rings of red to show where this material will be.

There is no need to fill the interiors of the rings in,, although you can if you like–they should look like strange irregular doughnuts. The edges of the red and green should overlap at least a little.

Once finished, you should have something like this:

Blue layer:

This layer is going to be some cracked ground areas in the main flat area of the landscape. If you were working on a detailed project, you could consider including these depressions as part of the terrain map for added realism. Here, let us simply make them a different material, for interest sakes.

Select the Blue layer, and set your brush to Blue, with RGB colour settings (0,0,255), and draw some blobs in an empty space where they don’t overlap with anything you have previously drawn.

It should look something like this:

Exporting the Material Mask Map.

Export the file as a png file. Now you can go into IClone, and load the Material Mask layer you have just created.

4. Tidying up:

Not bad – you can see the terrain and the material map do match up – but the edges between the different materials are too blurry, especially around the base of the pinnacles, where the Red and Green layers meet. Let’s adjust that a little.

To fix the problem above, I went back to myPhotoshop document, and increased the size of the green blobs a little. I also positioned the green layer on top of the Red layer, instead of underneath, so all the green is showing.

Here is my material mask after tidying those edges. It doesn’t look very different – the green area is just a little larger.

After tidying, make sure the three colour layers and the background layer are the only ones visible, and export your material map again. You may want to save it under a different name, in case you want the original one later.

Import the new material map into IClone.

Here are the results of my change – much better!

Of course, your material map may require you to make slightly different changes to your material borders, but I’m sure this demonstrates how easily it can be done. You can go back and forth between Photoshop and IClone and many times as is necessary to adjust your material map to your satisfaction.

5. Applying textures:

You can read about how to change the materials of terrains and adjust the settings in the IClone help files. It is straight forward enough, and if you have already used IClone to change textures of props or characters, you should be familiar with the process already. With the Butte terrain, the material names correspond to the colour layers we used as follows:

Height Map 01 = Red

Height Map 02 = Green

Height Map 03 = Blue

Height Map 04 = Black

Here is what my terrain looks like after playing with the terrain settings and quickly applying some new textures to the map:

Obviously better results could be achieved with a more detailed height map and fine adjustments to the material map. The purpose of this tutorial is, however, to demonstrate that adjusting the material masking layer is certainly possible using Photoshop and well within the capabilities of users familiar with materials, textures and layers in Photoshop and IClone.

Josie held her face into the wind and felt the wild exuberance of it like she had so many nights before. This time there was something different in the air, she was sure. The faintest trace of mists that had hung over ancient hedgerows, winds that had whistled across heather and down the chimneys of stone cottages, smoke belched from factories and railway engines.

‘I can smell England,’ she told Miss Miles.

‘Don’t be silly,’ said Miss Miles. As usual, Josie could hear in her voice that Miss Miles was nervous about being on deck after dark, though she tried not to show it. ‘England is still hundreds of miles away.’

‘Yes, Miss Miles,’ said Josie and sighed. She did not want to get into an argument with her chaperone, in which Miss Miles would invariably be the sensible one and she would be the self-evidently silly one. At the very least Miss Miles would be upset enough to make her come inside. She was always looking for excuses to make Josie come in out of the wind and the sea spray.

‘Do you think father will remember me?’ said Josie.

‘Of course he will, dear,’ said Miss Miles.

‘It’s been almost ten years,’ said Josie. ‘I would think you could bring just about any girl of about the right age and colouring and say she was Josephine Furness. Do you think he could tell the difference?’

‘Don’t be silly,’ said Miss Miles, and gave Josie’s hand a squeeze. ‘Of course he’ll recognise his own daughter.’ But to Josie Miss Miles sounded more nervous than ever.

Josie had only the vaguest memories of her father, a whiskery thundercloud of tobacco and eau de cologne that would roll into her life from time to time and then roll out again as quickly as it had come, ‘on business’ to Perth or the Eastern Goldfields or some other place, until one day just before her fifth birthday he had gone away ‘on business’ to the other side of the world and never returned. And now Josie’s Mama was gone, and her dear sister Gerry who had always looked after her when Mama had one of her turns was gone, and she was going to England to live with the whiskery thundercloud who had abandoned them so long ago.

It had all been sorted out by post. It was impossible to tell, from the stilted words of her father’s letters, if he really wanted her or not. She had made Miss Miles read and re-read them to her on the voyage until she knew every word by heart. It was possible that her father was stricken with grief for the troubles that had happened to the family he left behind, and was desperate to make what amends he could by welcoming his lost daughter, but just could not find the words to say so. Or, it was possible that he found the whole matter a great bother and distraction from whatever he did ‘on business’ and had long ago put out of his mind that he had left a family in Australia. She sighed again.

‘It’s getting terribly cold,’ said Miss Miles, with a shiver. The wind had shifted somehow so that it seemed to blow full in their faces whichever way they were facing. ‘We should be getting inside.’

‘Can I wait out just a moment longer?’ said Josie.

It was a plea she made every night, and every night Miss Miles made the same reply. Miss Miles had been Gerry’s friend- she had been Narelle to Gerry, and was not so very many years older than Josie herself- and did not have the backbone an older chaperone would have had.

‘Just for a moment, Josie,’ said Miss Miles. ‘I’ll wait for you inside.’

‘Thank you, Miss Miles,’ said Josie, and turned to give her a smile.

‘Just one more minute, then you come inside,’ said Miss Miles. She walked away, but Josie could tell she was hovering in the doorway, watching her.

‘Go on,’ said Josie. ‘I’m not made of cut glass, you know.’

Josie heard Miss Miles mutter something about wilful girls and close the door. She was probably still hovering, just on the other side, but Josie did not care.

Josie could no longer smell England on the wind. It was all sea now, heavy with mermaid’s tears and codfish and cold dark water that had spent a few lifetimes circling the world far below the surface before returning to the air again just now. Josie’s face was bitterly cold and if she had been sensible she would have suggested going inside herself ten minutes ago. She refused to admit that she was cold. She let the spray sting her face, trying to recapture the trace of England that she had smelled before. Probably the wind had shifted, and was coming out of the open ocean now. It was certainly getting stronger, minute by minute.

‘If only I could be sure father would be happy to see me,’ Josie thought. Mama had never said a harsh word about Josie’s father, only looked terribly woeful whenever he was spoken of. Not that he was spoken of much. There had been letters when Josie had been younger, but they were the same sort of stilted letters father had sent after the tragedy, and they had stopped coming a long time ago.

The wind seemed to stop entirely for an instant, and start up again from another direction, a proper gale. This wind had the trace of some flower in it that smelled a bit like vanilla bush – it wasn’t vanilla bush, but it was something like it. Josie did not have time to think about what it could be, because at that moment the ship reared up like some fool of a thoroughbred and tipped her over the railing into the sea. Josie had no sensation of passing through the air but felt immediately plunged into the water.

‘I suppose I am going to die now so there was no use worrying,’ thought Josie, surprised at how unafraid she seemed to be. There was no question of swimming in the heavy coat and long skirts she had been wearing to keep off the cold on deck. Josie was not sure whether she was upside down or right side up. She tried to compose herself and say a prayer, but all that came into her head was ‘now I lay me down to sleep’ which was not particularly appropriate for being tumbled through the icy waters of the North Atlantic. Josie felt very sorry for Miss Miles, who would surely think it was all her fault that she had been lost overboard.

‘How silly I’ve been worrying about such a lot of silly things,’ thought Josie. She remembered in particular one time she had been beastly to little Ada Plummer over something that now seemed of no consequence whatsoever.

‘I hope it won’t be too horrible drowning,’ she thought. Then she was afraid, and thrashed desperately about without thinking at all.

Suddenly she was not in the water anymore. She did not feel desperately short of breath, and she did not feel particularly cold. For the merest instant she thought she might be in Heaven. She was lying on her back in soft grass, with sun on her face, and the air was filled with the smell of the flower that was something like vanilla bush- and also lemon blossoms, and jasmine, and three or four other pleasant things that she couldn’t identify.

‘But I can’t see,’ Josie thought. ‘Surely in Heaven I would be able to see.’ She put her hand in front of her eyes and felt the flutter of her eyelids to make sure that she did not just have her eyes closed. She was still blind.

‘And I wouldn’t be wearing these clothes’ she told herself. In Heaven she would have expected to be wearing flowing robes – or possibly nothing at all – but she seemed to be wearing the exact clothes she had been wearing on the deck of the Southern Cross, though they were now dry.

Josie sat up. She could hear birds singing, but not of any sort she recognised. She could also hear running water. She seemed to be only a yard or so from the edge of a stream. There were branches moving in the wind, but not right above her; maybe fifty feet away. The grass had little flowers in it, tufted ones shaped a bit like dandelions, and it was from these that the vanilla bush smell came from. The sun on her face cooled momentarily, then warmed again, and she imagined there must be little clouds scooting across the sky.

‘Curiouser and curiouser,’ she said to herself, because she had to hear the sound of a human voice, and the only thing she had ever heard of before that was remotely similar to what had just happened to her was what happened to Alice when she fell down a rabbit hole.

Josie stood up carefully expecting to be aching all over, but was not really surprised to find that she wasn’t. She felt more cheerful than she had in a long time. It had been of course a very cheering surprise to find herself alive at all. But even if she had been in no danger before, she felt she would have found the place she was in cheering. Somehow she had fallen into spring out of winter. She took a few careful steps and heard the whirr of wings- some of the unfamiliar birds had decided she had come too close. A few steps more, and her outstretched hands brushed against a bush. It had soft fleshy leaves that were not smooth, but covered with down, and it smelled marvellous but strange, like the birds sounded. She brushed her arm up and down, side to side, to get a feel for how big the bush was, and as she did so there was the startled sound of a hoofed animal leaping up and cantering away. It sounded like a sheep-sized animal rather than a horse-sized one. She could smell it too, a little- a warm deserty smell that was not at all like sheep’s wool. The noise of the animal startled Josie in turn, and she laughed like she sometimes did when she had a fright that turned out not to be so bad after all.

‘Excuse me!’ she said.

The cantering slowed to a walk and then stopped. ‘What did you say?’ said a voice. It was a voice that seemed to belong to a girl some years younger than Josie, and one that could have made a good living singing on the stage.

‘I said excuse me,’ said Josie. It had not sounded to Josie as if there had been anyone else there, but she supposed there must have been. ‘I didn’t mean to startle it.’

‘I’ve never heard a Daughter of Helen say ‘excuse me’ before,’ said the voice. It really was a very pretty voice. ‘You have a peculiar way of talking’ it added cautiously.

‘You have a rather peculiar way of talking yourself,’ said Josie.

‘I didn’t mean to be disrespectful,’ said the voice. It sounded nervous and so did the animal, which took a few paces back and forth. Josie wondered if she was riding the animal and if in that case she was about to suddenly bolt off. The voice continued. ‘If you don’t mind me saying so, and I don’t mean to be disrespectful, but you Daughters of Helen and Sons of Frank are usually too caught up in your own affairs as Ladies and Lords of Creation to care whether you startle gazelles or not.’

Josie hadn’t heard any sound of harness, or of anyone moving about, just the animal. She had been reminded of Alice and the looking glass ever since she arrived in this place, and thinking of the conversation Alice had with a fawn in the wood she asked a question she had never imagined she would ask anyone.

‘Are you a gazelle?’ she asked.

‘Yes’ said the voice. ‘My name is Alabitha. My mother is Falabitha, and my father is Caladru, who is the Prince of all the gazelles in this country.’

‘My name is Josephine Furness,’ said Josie. ‘You can call me Josie instead of Miss Furness if you like. My mother’s name was Annabelle, and my father’s name is Leonard. Pleased to meet you, Alabitha.’

‘I’m so glad you’re pleased to meet me,’ said the gazelle warily. ‘I suppose I’m pleased to meet you as well.’ There was a pause and a shuffling of cloven feet while Josie wondered which of the many questions she had she would ask, but Alabitha spoke again first. ‘Have you come from one of those faraway northern countries where men and animals get along with each other, Lady Josie?’

‘I’m from somewhere a long way off,’ said Josie. ‘It can’t be any of the countries you are thinking of since we don’t have any talking animals. I don’t know how you would get there from here.’

‘Oh’ said Alabitha. ‘Are you lost? Where are you trying to get to? I know all of the ways around here.’

Josie remembered the Red Queen saying that all of the ways were her ways, and for the first time since she arrived in this place felt uneasy. What exactly was she going to do? Where was she, and how was she going to survive in this place?

‘I don’t know,’ said Josie. ‘I expect I must be lost. I don’t know how I got here, or where here is.’

‘That’s too bad’ said the gazelle. She padded a little closer to her. ‘I don’t know how you got here either. I’m sure you weren’t here when I got here, and I’m sure I would have woken up when you got here – unless I’m getting a stuffed ear.’ The gazelle snorted and shook her head three or four times.

‘The last I remember I fell in the ocean’ said Josie. ‘And then I was lying next to the water here.’

‘I’ve never seen the ocean,’ said the gazelle. ‘It’s a frightful long way to the ocean from here. This is Lion’s Pool. See the carved stone where the water comes out of the rock?’

‘I don’t,’ said Josie. ‘I don’t actually see anything. I’m blind.’

‘Oh’ said Alabitha. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘It’s not your fault,’ said Josie. ‘I’m used to it.’

‘I can tell you what the carved stone looks like’ said Alabitha. ‘It’s carved to look like a lion, as large as life. The Sons of Frank and Daughters of Helen made it long ago, to show that it was one of the places where the Lion appeared.’

‘The Lion?’

‘The Lion, you know, Aslan,’ said the gazelle, in the gentle but nervous way you remind someone who has had a bad shock of something that they really ought to know.

At the sound of the name Aslan Josie felt something like she had felt when she could smell England on the wind over the ocean. It was like the first breeze from a far country that was at the same time terrifying and familiar, where everything is larger and brighter and stronger than home, yet at the same time in some strange way more truly ‘home’ than the home she had always known. She felt as if she never wanted to hear the name again, and as if she could listen to it forever. At that moment the first wanting was stronger, so though she was burning to know exactly who this Aslan was and why it was so important, she could not bring herself to say the name.

‘Oh,’ said Josie.

‘It was years and years and years ago,’ said Alabitha. ‘Before anyone who is alive now was alive. Except for some of the trees, probably.’

‘Which direction is it?’ asked Josie. ‘The carving?’

Alabitha told her and she walked up the stream for twenty yards or so on soft springy grass to the place. There was a mass of granite meeting her feet at about a forty five degree angle and she had to clamber up it a few steps and reach forward to touch the carving. The surface was worn and rough but the shape of the Lion’s face was perfectly distinct. She could feel the whorls of the mane worked very clearly, the mouth closed in a calm and serious way and the eyes open wide. It seemed even larger than life to Josie, but she had never been close enough to a lion to touch one. She stepped back down onto the grass.

‘I think it is splendid that you can make such things,’ said Alabitha, who had followed her, and was standing closer to Josie than she had before. ‘It must be wonderful to have hands.’

The strangeness of everything was suddenly overwhelming. Josie could feel tears starting to well up.

‘I don’t know what to do,’ she said.

Alabitha shuffled awkwardly as if she was not used to humans being anything but imperious. ‘You will probably think of it,’ she said. ‘Daughters of Helen always do.’

‘I suppose so,’ said Josie, in a small trembling voice.

Alabitha fidgeted nervously some more.

‘You’re sure to be here for some important reason, or you wouldn’t have turned up at the Lion’s Pool. I’ll tell my father you’re here and he will send someone wise to talk to you, and they will figure out what it is.’

‘That sounds good,’ said Josie in the same small trembling voice, thinking of her own father. ‘Thank you.’ She managed to pull herself together and not cry until Alabitha had trotted off. Then it was all too much.

After a while nothing had changed, but Josie felt better for the crying. She took off her coat- which was much too warm for this place- and her boots and stockings, and lay down in a shady spot where she could feel the deliciously cool grass on her feet. She listened to the tinkling water and the wind in the leaves and the strange birds and listened out for any other creature, but there was nothing.

‘The wise gazelle will be here any minute, so I must be sure to stay awake,’ she thought, and laughed a laugh that was only a little a sob to think she was waiting on a wise gazelle. But she fell asleep anyway.

It may seem that we have not been writing very much over the last six months or so, and this is both true, in terms of publishing things, and not true, in terms of projects that have been trickling along the background. In my case, I have been working on “The Changing Man,” a teen fic novel set in the universe of “Misfortune“, and also on the second volume of Aronoke, More recently I have started a story about a traveller boy in the world of Tsai, called “Sky’s the Limit” (which may never see the light of day), whereas Chris has been diverted into completing his Narnia fan-fiction story, Bride of Tash.

It may seem that we have not been writing very much over the last six months or so, and this is both true, in terms of publishing things, and not true, in terms of projects that have been trickling along the background. In my case, I have been working on “The Changing Man,” a teen fic novel set in the universe of “Misfortune“, and also on the second volume of Aronoke, More recently I have started a story about a traveller boy in the world of Tsai, called “Sky’s the Limit” (which may never see the light of day), whereas Chris has been diverted into completing his Narnia fan-fiction story, Bride of Tash.

Today I put up the first chapters of Bride of Tash at fanfiction.net, and also at Archive of Our Own, which is a fan fiction site frequented by our children. There are great drosses of trash to be found on fanfiction collection sites such as these, mostly in the style of “What would happen if Major Character X had the hots for Major Character Y?” but there are occasional gems to be found floating in this sea of mediocre slush.

Bride of Tash can also be found here, in the Freebies section, where it will be updated prior to other postings.

Tash had always been told he was perfectly and completely useless.

‘Perfectly and completely useless,’ his father would say, in a voice that was an instrument for making absolutely clear statements of mathematically precise fact. His brothers would nod their heads solemnly in agreement, and his sisters and mothers would creak wheezily from their alcoves to show that they also agreed that Tash was perfectly and completely useless.

Tash would bow his head and let his arms droop, as if to agree that what his father said was true.

‘And yet,’ Tash would think to himself, ‘I am not useless at all.’ And he would daydream of what he would do one day to prove to everyone that he was not perfectly and completely useless and lose track of what his father was saying.

It is not my intention to excuse anything Tash did or didn’t do on the grounds that he had an unpleasant childhood. I am not telling you this so that you will feel sorry for him, or so you can psychoanalyse him. It is only that if Tash hadn’t had an unpleasant childhood, he would have gone on to live a very ordinary life like his brothers and would not come into this story at all.

For the first four years of his life no one said a kind word to Tash. Four years among the thalarka is about the same as fifteen or sixteen of our years, for the world of the thalarka rolls sluggishly around their great green marrow-fat pea of a sun. In all that time no one told Tash that he was anything other than perfectly and completely useless.

In point of fact, he was useless. To live in the Plain of Ua requires stamina, to work all day in the endless fields of mud: planting grith, and fertilising grith, and weeding grith, and warding off the beasts of mire and mist that are eager to eat the tender young grith plants, and harvesting the spindly fruit of the grith that must be picked in darkness and husked and pickled the same night it is picked so it will not spoil. Tash was weak, and could not do any of these things for more than half an hour at a stretch. Furthermore, he was sickly, and was forever getting fevers that made him no good for any work at all for days on end. Worse, he was impatient and easily distracted, and long before he was too weak to work he would usually have wandered off to tease some many-legged crawling thing with a bit of stick, or make little dams and canals in the mud with the hoe he was supposed to be weeding with. And he was clumsy: he would trample the little grith plants, and pull them up instead of the weeds, and at harvest time he would get bits of husk in the pickling pot, and drop fruit in the mud, and stab his fingers on the prickly parts of the fruit so that they swelled up and were perfectly and completely useless for any more husking.

Once in each long year of the thalarka was the festival of Quambu Vashan, which was held in the city where the Procurator of the Overlord had her alcove, some days journey away on the edge of the Plain of Ua. There was always great feasting at the time of the festival of Quambu Vashan, and acrobats and clowns, though only old Raaku of all the villagers had ever seen them.

Two or three times a year the rain would stop and the sun would peer down through a canyon in the clouds. Then the thalarka in the fields would down tools and try not to look up at the great green marrow-fat pea of the sun and mutter proverbs. Tash would always look up at the sunlit sides of the canyons of cloud- which were almost too bright to see- and dream of what it must be like to be up there.

Eight times a year was the frenzy of the harvest, and after the harvest came the feasting, and after the feasting the coming of the Overlord’s tax collectors, to carry off rather a lot of the pickled grith that was left over from the feasting.

Two or three hundred times a year there would be some sort of holiday to break the round of working in the fields, with the proper dates for each holiday kept in order by the priests. There would be dancing in figures, and wagers on fights between caged mire beasts that were things like hairless weasels, and the priests would usually sacrifice something and make patterns on the walls of the priest-house with dripping bits from its inside.

Every day it rained.

The plain of Ua was a plain of grey mud, and the skies were of grey cloud, and the stick-like grith were grey, and the huts of the thalarka were grey. The thalarka themselves were also grey. The huts of the thalarka were dry inside with a fitful clammy dryness, in which lamps burned only with a feeble bluish flame. Tash thought fire was splendid, since it was not grey. That was how he managed to burn one of his hands rather badly just before the harvest. At this particular harvest he was needed more than usual, since his two oldest brothers had been married off into other villages since the harvest before, but because of his injury he ended up being even less useful than usual.

This was not long before the festival of Quambu Vashan. Besides clowns and acrobats, great numbers of sacrifices of a particular kind were always required at this festival, so it was the custom of the tax collectors of the Overlord to demand from each village they visited at the harvest an appropriate sacrifice. This would not be important if it were not that the sacrifices required for the festival of Quambu Vashan were thalarka of about four years of age. It was required that they have all their limbs intact, and have no obvious serious blemishes, but otherwise it was all the same to the Overlord whether they were useless or not. This part of the festival did not feature in Raaku’s stories, and the older thalarka of the village tended not to discuss it in the presence of younger ones.

‘We should give Tash to the tax collectors for sacrifice at the festival of Quambu Vashan,’ said Tash’s father to his mothers one night. ‘For he is perfectly and completely useless for anything else.’

A family that freely gave the sacrifice for the festival of Quambu Vashan would be noted on the books of the tax collectors and not be called upon to give another for a generation, during which time more useful members of the family suitable for sacrifice would be spared to work in the fields. It was also the custom in Tash’s village for the families who had not given a son or daughter to the tax collectors to bring presents to the family that had, and speak approvingly of them, so Tash’s father’s suggestion was quite a good one. It is only fair on Tash’s mothers to report that they did not croak their agreement immediately, not until Tash’s father had reminded them of these things.

So after the harvest when the tax collectors of the Overlord came to the village Tash was sent off with them.

‘You are being apprenticed to the tax collectors,’ Tash’s father told him. ‘You will leave with them when they have finished lunch.’

Tash did not realise why he had been sent off until he had been travelling the rest of that day with the tax collectors. He had spent most of the afternoon staring up at the roiling patterns of the clouds, imagining that they had hidden meanings. They were like secret symbols from a mysterious power in the sky sending orders to its minions in the mire, in a tremendously complicated language that never said exactly the same thing twice. The tax collectors had already collected four other young thalarka for the festival of Quambu Vashan. Three of them were girls, and Tash could not understand their speech – it was another part of Tash’s uselessness that he had a bad ear for women’s language – and the fourth was a boy. He was slow-witted and smaller than Tash, but he had paid more attention to the world around him.

‘Where do you think we will stop?’ said Tash as it started to get dark, meaning ‘where are we going to stop tonight’, but the slow-witted one took him at his word and said, ‘At the festival’.

‘Why did you say, ‘at the festival’?’ said Tash, since he was bored and couldn’t think of anything better to do than quibble with the slow-witted boy. ‘Why not say we’re going to the city of the Overlord’s Procurator?’

‘I don’t understand,’ said the slow-witted boy. He hung his head and drooped his arms in exactly the same way Tash had always done when his father told him how useless he was.

‘So, what does the festival have to do with it?’ said Tash impatiently.

‘I’m going to be a sacrifice at the festival,’ said the slow-witted boy. He said it in the same way that Tash’s brothers would say things like ‘I’m going to weed the south-eastern corner of the field today’.

Tash looked around at the others and thought that the tax collectors had treated all five of them in exactly the same way since they had left the village. Here they were, all walking in a line through the mud. And he realised that his father had very probably lied to him, and that he was going to be a sacrifice as well. For a while he could say nothing at all.

‘I seem to be in terrible trouble,’ Tash thought.

Over the next few days of tramping across the Plain of Ua Tash tried to escape many times, but the tax collectors were experienced collectors of sacrifices, and he had no luck. They went through nine more villages and collected nine more sacrifices for the festival of Quambu Vashan. Five of these were boys, and they were all slow-witted except for Zish, who was contrary.

‘I was opposed to the ways of the village because they were brutish and stupid,’ said Zish, in a way Tash had never heard before, that was bitter and mirthful at the same time, as if it pleased Zish more than anything to call the ways of his village brutish and stupid. ‘So I’m to be sacrificed now,’ he went on. ‘At least my blood will be of some use to the Overlord Varkarian, if it is of no further use to me.’

‘I’m sure there is some way to escape,’ said Tash. ‘If we work together’-

‘There is no way to escape,’ said Zish in his bitter mirthful way. ‘This is our destiny, Valgur’ – he had confused Tash with one of the other boys, whose name was Valgur, and took no notice of Tash’s efforts to correct him – ‘to serve the Overlord by being sacrifices at the festival of Quambu Vashan. Our destiny is inexorable. Our destiny is irresistible.’

Tash stopped listening to Zish as he talked more about inexorable destiny and the usefulness of being sacrificed. Tash was not sure whether this was what Zish really believed or not. Perhaps he did not know himself whether he believed it or not. Sometimes Zish talked in such a way that Tash thought he must be mad, and sometimes Zish told Tash that he was mad.

‘I have said the same thing to you a dozen times, Valgur, and you haven’t said a word back, just gone on staring at the clouds,’ said Zish. ‘You must be mad. It is no wonder you are only fit to be sacrificed.’

At any rate Zish was too contrary to be in any way helpful to Tash.

If he had not known he was going to be sacrificed at the end of it Tash would have had a lovely time. The long hours of walking were dreadfully wearying at first, but he felt himself growing stronger each day, and the sacrifices were fed twice a day with the freshly pickled grith the tax collectors had gathered, which was more and nicer food than Tash had eaten before. Each day he saw new villages, with new and different temples, and new fields cut into different shapes, and great coiling worms of rivers, and broad lakes spotted with rafts, and companies of spear-men and javelin-women marching on the highroads, their armour as silvery-grey as the lakes and spotted with metal spikes instead of rafts. He had seen nothing but his village and the fields immediately around it for his whole life and found he quite liked travelling.

At the edge of the Procurator’s city Tash’s party met up with several other parties of tax collectors. All the sacrifices were collected together and tied in a long chain to keep them tidy, ankle to ankle and wrist to wrist, and in this way they all shuffled together into the Procurator’s city. This city was made of grey stone, huts and palaces alike, and they were scattered together in no particular order over the plain, at first with plenty of space between them but then closer and closer together until they almost blocked out the clouds.

‘Do not let the splendour of this place fool you, Valgur,’ said Zish. ‘Here, too, the ways of the common people are brutish and stupid. But we are irresistibly called to a higher destiny. Inexorably!’

In the middle of the city was the Tower of the Procurator of the Overlord, ten or twelve times higher than any other built thing Tash had ever seen. It was carved on every side with images of mist-beasts and mire-beasts and thalarka, all larger than life, and all making gestures of obeisance to the sigil of the Overlord Varkarian, which was at the top of the tower and was worked in huge blue stones like fire.

‘Sweeter than narbul venom is it to serve the Overlord,’ intoned the most senior of the tax collectors, when the party could first see this sigil in blue stones like fire. All the more junior tax collectors dutifully intoned in unison that it was sweeter than narbul venom to serve the Overlord, and so did the long line of sacrifices. Strictly speaking Tash had no idea whether this was true or not, having never tasted narbul venom nor anything other than grith. But he intoned along with the others. They only had a few moments to look at the tower. Tash would have stared longer, but was dragged along as he was chained to everyone else. Then they were steered through a big black door and down a long ramp which stretched down into a chamber somewhere underneath the tower. The ramp ended somewhere in the middle of the chamber, which stretched off into darkness on every side, over-warm and evil-smelling. Some dozens of boys and girls for the sacrifice were there already, chained to posts set in the floor in groups of six or seven. On top of these posts there were lanterns, and every post that had thalarka chained to it had its lantern lit, with a dancing flame that was more green than blue. Tash’s long line of sacrifices was split up into groups of six or seven and chained to posts, and at the same time the lanterns on top of the post were lit. But there were still many many more empty posts with unlit lanterns.

The chamber was drier than any place Tash had ever been. You or I would have found this its one redeeming feature, but to Tash it was unnerving. The dryness hurt his ears and made his throat itch.

The thalarka who lit the lanterns was an old priest woman, bent over like a grith plant that has grown in too dark a shadow, and she lit the lanterns with a thin silvery stick longer than she was tall. Tash found the lighting of the lanterns very interesting and wondered if the old priest stayed down in the chamber all the time, waiting for a reason to light the lanterns, or if she went somewhere else. She seemed so completely a creature of the dark chamber that Tash could not imagine her being anywhere else. Tash ended up chained with a group of dim-witted boys around one of the pillars at the edge of the darkness.

As soon as all the sacrifices were properly chained a group of younger priests handed out something to eat that was not grith. They were cakes of something very much nicer than grith, though I dare say you or I would still have found them very nasty, and Tash devoured his greedily. So did all the others. When they had finished eating two more priests in more resplendent garments – still mostly grey, but shiny – came and gave speeches, one in male language and one in female language.

The speech that Tash heard went something like this:

‘Welcome in the name of the Overlord Varkarian. Truly it is sweeter than narbul venom, and more pleasant than the song of horn and cymbal, to serve the Overlord Varkarian. Truly are you favoured, for through your sacrifice the Overlord will be glorified. Truly will your sacrifice bring the inscrutable designs of the Overlord closer to their inexorable fruition. Though you may have been useless until this moment, very soon you will attain to a destiny greater than that of many a skilled spear-man or artifex. The part you play in the designs of the Overlord is a very great one.’

There was much more like this and Tash soon stopped paying attention to it. He was more interested in the costumes of the priests than in what they were saying. Their chest pieces were particularly splendid, much more splendid than the chestpieces the priests of his village wore when they sacrificed mire beasts. They were set with such marvellous stones, blue and green and other colours he could not name, and shone delightfully in the lanternlight.

The priest explained while Tash was not listening that they would be given things to eat as nice as the cakes, or nicer, for the next few days until the festival, and that they would be taken out in batches and cleaned and ornamented before the ceremony, and then again that theirs was a rare and glorious destiny.

Because he was not listening Tash was taken by surprise to be taken out and scrubbed and plastered with some sort of oil and hung with jangling bits of fine chain. The only good thing about the oil was that it made it quite impossible to tell how evil-smelling the chamber was. The smell of the oil stung and tickled and burned and it was almost impossible to think of anything else when you had been plastered with it.

‘What’s that you’ve done to your hand, lad?’ asked the young priest who was seeing to the oiling of the sacrifices. ‘Burnt it, eh?’ The young priest found this amusing. ‘Well, mind you keep it away from the lanterns now. Stick one little finger in the fire and you’ll be sizzled to a crisp in an instant, with that oil on you.’

Tash took respectful note of this advice.

Tash had been chained to a post on the other side of the ramp from Zish, and the dim-witted boys who were chained with him were too dim-witted to be any use talking to. He spent the night peering out into the further reaches of the chamber, wondering what was there and thinking of all the marvellous things he had seen in the last few days and what a pity it was that he would be sacrificed in a few more days. The sacrifices around him shuffled and wheezed and jangled in their sleep and the smell of the oil hung thick and heavy in the air. No one came and turned down the lanterns, but they seemed to dim of their own accord, and burnt with feeble flames that were greenish-grey, if such a flame were possible.

Tash found it impossible to get free of his chains. Even if he had, it would surely have been impossible for him to have forced his way through the heavy doors, past the watchers beyond, and made his way to somewhere safe.

‘It seems such a waste, when the world is so big and interesting, to be ending so soon,’ he thought to himself. And a black mood took him and he thought to himself: ‘Perhaps I am useless after all’.

Aronoke was left by himself with a deluge of disturbing thoughts to contend with. How could Ashquash be drugged? How could anyone do such a thing to her, here in the middle of the Jedi temple? Why would anyone want to?

And then the truth hit him. It was a punishment. Not a punishment for Ashquash, most likely, but a punishment for him. He had reported the strange message, reported all the odd things on his datapad. Ashquash was his friend and had been attacked in order to convince him that this was not a good idea.

He slept little for the rest of the night; would have liked to go running, but knew that was not wise. That Razzak Mintula would not have liked him to go alone, not just then. So he meditated instead. After a long time he was able to calm his thoughts enough to fall asleep.

He awoke quite late the next morning, but Ashquash was still not there. Razzak Mintula was not there either. Mintaka, the instructor who sometimes stood in for her was there instead.

“Razzak Mintula will not be here today,” Mintaka announced at the start of their first lesson. “She was up very late tending to Ashquash, who is sick. Ashquash has been taken to the medical bay, and she is fine, but she will not be back for a few days.”

Aronoke could feel the weight of Draken’s eyes and knew that Draken wanted to ask him all sorts of questions, but he refused to meet the other boy’s eye and firmly concentrated on his lessons.

“What happened to Ashquash?” Draken asked as soon as they went off to the refectory for the midday meal. “She seemed fine yesterday.”

“I don’t know,” said Aronoke. “She woke me up in the middle of the night, and Razzak Mintula took her to the sick bay. That’s all.”

“Oh.”

Aronoke did not want to tell Draken about Ashquash being drugged. Draken was his friend, but inclined to gossip with people from other clans. Aronoke thought that if he were Ashquash, he would feel ashamed and wouldn’t want the real story spread about.

But a few days later it became apparent to everyone that there was more to the story than merely Ashquash falling ill. Razzak Mintula was back by then and had reassured Aronoke that Ashquash was fine and was being decontaminated. Aronoke sensed that she was angry that something like this could happen to a student in her care. He felt the same sort of powerlessness himself.

“Today our schedule will be a little different from usual,” said Razzak Mintula as they gathered in the clan room after breakfast. “We will be having our first session in here today, so it will almost be like a kind of holiday. An investigator will be coming to ask some questions about Ashquash. He will want to know if you noticed anything the day before she was sick, because there is some concern that it might have been done on purpose.”

“On purpose?” asked Draken, his voice rising in his surprise. “Ashquash was poisoned?”

“That’s bad,” said Andraia, one of the smaller humans. “I don’t want to be poisoned!”

“It is bad,” said Razzak Mintula. “But you don’t need to worry. There is no reason to think that any of you will be poisoned, but you must be sure to answer the investigator’s questions carefully.”

“Yes, Instructor Mintula.”

When the investigator arrived, he was a man who looked largely human except for his skin, which was marked like that of a spotted cathar. He was accompanied by four droids and Aronoke wondered why he needed so many of them.

“This is Investigator Rythis,” said Razzak Mintula to Clan Herf, who sat cross-legged on the floor. “He has set up his office in our usual classroom, and will want to ask you all some questions, as we have previously discussed.” Even while she spoke, three of the droids began cruising about Clan Herf’s rooms, scanning everything.

The investigator was a dour looking man for a Jedi, Aronoke thought. Either he was of a naturally sombre disposition, or he was not pleased at having to interview a bunch of initiates. Perhaps though, to be fair, thought Aronoke, the Investigator judged the situation was serious enough to warrant such an attitude.

“This is a serious matter,” said the Investigator sternly. “I intend to determine how your clan-mate Ashquash was drugged, so we can find out who is ultimately responsible. I will take you one at a time to ask you questions. I want to know if you noticed anything unusual about Ashquash or anything else, so you should think about that while you are waiting for your turn.”

The way he spoke was very intimidating, and Aronoke noticed several of the smaller clan members edging closer to their fellows.

“Which one of you is Initiate Aronoke?” asked the Investigator. “I would like to speak to him first.”

He pronounced Aronoke’s name wrong, which hadn’t happened in some time.

“I’m Aronoke,” said Aronoke, by means of correction as he climbed to his feet. He met the man’s intense gaze steadily. This was just a Jedi investigator, here to help Ashquash, and Aronoke hadn’t done anything wrong. Besides, he wasn’t anywhere near as frightening as Careful Kras, and Aronoke was determined to show the smaller ones that they need not be afraid.

“Come this way,” said the Investigator, gesturing towards the door that led outside.

“Yes, Investigator,” Aronoke said.

He followed the man across the hall into the classroom on the other side of the hallway.

“You are Ashquash’s room mate?” asked the Investigator, and Aronoke agreed that this was so. “This whole situation seems somewhat irregular,” grumbled the investigator disapprovingly, and Aronoke wondered what he meant. Because Ashquash was a girl? Because they were different species? Because both he and Ashquash had unusual backgrounds and had come late to the Jedi Temple?

The Investigator did not explain himself, but lots of questions followed, concerning what had happened the night Ashquash was drugged. Aronoke did his best to answer all of them. How had Ashquash woken him up? Had she ever done so before? Did she usually touch him like she had when she had shaken him? How did she usually behave around him? What sort of sparring did they do? Did they ever go sparring together alone? Did they go out in the middle of the night?

Aronoke began wondering if initiates did all these strange sorts of things more often than he realised. He also found himself questioning exactly what it was the investigator was investigating.

“Do you have any idea why someone would want to drug Ashquash?” the investigator asked.

“I thought it might be part of the unusual things that sometimes happen to me,” said Aronoke hesitantly. “I thought it might be a punishment, because I did not do what the message in one of them told me to do, because I knew it was wrong.”

“Unusual things?” asked the investigator. “What message?”

Aronoke was surprised, thinking that the investigator would have known about all that.

“I reported all of them, either to Master Insa-tolsa, or Master Altus, or Razzak Mintula,” he said. “Unusual things happen to me sometimes. Someone is trying to manipulate me. I thought what happened to Ashquash might be a punishment because I refused to do as I was directed.”

“These incidents will have to be recovered from any reports that were made by your superiors,” said Investigator Rythis primly, his fingers flickering over his datapad. He seemed annoyed with Aronoke, like this information was not helpful at all.

Aronoke shrugged. He tried to explain everything in detail, but by the end of it he still felt that the investigator was not pleased with him. Whether the investigator had expected to find a connection between Aronoke and the drugging, or thought Aronoke was purposefully concealing things was not obvious.

“What was it like?” Draken asked, he face alight with anticipatory relish, when Aronoke returned. “Was he scary?”

“No, not really,” said Aronoke calmly. “He just asked me lots of questions.”

“What about the droids? They didn’t torture you did they?”

“No, of course not!” said Aronoke. “There was one taking notes. The others seemed to be off scanning things.”

Draken was caught between relief and disappointment.

“He can’t be much of an Investigator then,” he muttered, “if he’s not as scary as he seems. Really it’s an affront to Ashquash to send somebody so tame. How can he be a proper investigator?”

“You can’t have it both ways you know,” pointed out Aronoke. “It’s either scary and then you’ll be scared because he’ll probably want to talk to you next, or it’s not scary and it’s boring.”

“Hm, I guess,” said Draken, unconvinced.

The investigation did not result in any great revelation that Aronoke ever learned of. No culprit was brought to justice, although eventually it was revealed that Ashquash’s toiletries had been tampered with, and that this was how the drug had been administered. Aronoke looked at his own toiletries with new distaste. He had never been fond of them – the water was bad enough by itself – and now he was even less inclined to use them.

It was difficult to relax and be calm after that. He felt angry and unsettled. More and more it seemed that what had happened to Ashquash was his fault, if only indirectly. If he had not been here, than would this have happened to Ashquash? He didn’t think so. It wasn’t fair. She only had this one chance to succeed at being Jedi, like he had, and because she was Aronoke’s friend it was being taken away from her.

It would be better, Aronoke reasoned, if he had no friends. He knew this was not right. After all, clan-mates were supposed to work together to solve problems. But most of Clan Herf was so small. What good would it do to involve the little kids in his problems? What if one of them was hurt next? That thought was unbearable. He wished Master Altus was here to talk to. That in itself was pointless, because it seemed likely that none of this would have happened if Master Altus was here. Aronoke knew he should try to be brave and independent, even if he felt out of his depth.

Ashquash came back a week later, quiet, withdrawn and grumpy, in many ways reverted to the angry uncommunicative person whom Aronoke had first met. Aronoke took care to behave like he had done then. He sat quietly and did his lessons nearby, not ignoring Ashquash, not paying undue attention to her, but focusing on his reading.

Ashquash sat on her bed and did nothing for a long time.

“I don’t think I’m going to make it,” she said finally. Sadly.

“Don’t say that,” said Aronoke, shocked. “I don’t see any reason why you shouldn’t make it. You’re smart and strong as anyone else.”

“Someone doesn’t want me to,” said Ashquash. “It’s obvious. They don’t want me to succeed, so they did this to me. And right now, it’s only the stubborn, angry bit of me that wants to stick it through, just so that they don’t get what they want.”

Aronoke was overcome with remorse.

“That’s not necessarily true,” he said. “It is possible that some Jedi masters think that you shouldn’t be an initiate, but that doesn’t mean they would go so far as to sabotage your efforts. And for every one that thinks you shouldn’t be given the opportunity, there must be even more who think you should, otherwise you wouldn’t be here at all.”

“Hrm,” said Ashquash, unconvinced.

“And it might not be because of you at all,” said Aronoke, ploughing on despite his better judgement. “Strange things have been happening to me practically since I got here. Especially since Master Altus left. Weird things keep appearing on my datapad. A strange holotransmission was delivered by a droid, trying to manipulate me. I reported them all, and it seems to me that this attack on you might have been a sort of punishment. I mean, you are my room-mate, we are friends, right? Maybe you got hurt so that next time I listen to what it says.”

Ashquash looked up at that, warily.

“I reported those things to Master Insa-tolsa,” said Aronoke. “He said they are trying their best to fix them. I really hope it won’t happen again.”

“Why would they want to manipulate you so badly?” asked Ashquash critically. “To do what? Because you’re so special?”

“Because I’m different,” said Aronoke. “I…there are some different things about me.” He thought for one wavering moment that perhaps he should tell her about his back, but it was too frightening, too strange. Too much to burden Ashquash with.

“I am different too,” said Ashquash.

“Yes, that’s true,” said Aronoke. “I don’t know why they would want to manipulate me specifically,” he continued, semi-truthfully, for although he knew it was almost certainly something to do with his back, he didn’t know why his back was so important. “But it’s obvious that they do, because of the message and the other things that have happened.”

“Huh,” said Ashquash.

“I was thinking,” Aronoke said, “that if it’s true that you were hurt because of me, than perhaps it might be better if you were not my room-mate anymore.”

Ashquash looked up at him. Her complexion darkened like a sandstorm was rolling across it. Her eyes darkened and her young face settled into hard, tense lines that made her look much older. Her anger was a tangible, frightening thing.

“I just don’t want you to be hurt because of me,” he explained hurriedly.

“Maybe it would be better,” said Ashquash tightly.

“We could pretend that we had argued,” said Aronoke. “That’s not true of course. We would know we hadn’t argued. We haven’t argued, have we? But it might be enough to keep you safe.”

“How will we decide which of us should change rooms?” said Ashquash flatly, suddenly looking drained and tired instead of angry. Aronoke felt sick, because he didn’t want to travel this path. Wouldn’t the voice have won a victory if he did? But the alternate path seemed impossible. He wanted to protect his clan-mates from this mess, not get them further involved. They were too small to have to deal with such a big problem, he reasoned. Or had too many problems of their own, like Ashquash.

“It’s okay, I don’t mind changing,” he said. “You shouldn’t have to do anything – it’s because of me that this happened, so I should be the one who changes.”

Ashquash said nothing for a long moment.

“Alright, go then,” she said, bitterly.

Aronoke nodded, got to his feet, and went to Razzak Mintula’s room.

“Yes, Aronoke, what is it?” asked Razzak Mintula wearily.

“Razzak Mintula, can I change rooms?” asked Aronoke.

She looked at him for a long moment, studying his expression. “Perhaps that mightn’t be such a bad idea,” she said, finally. “I am reluctant however, to swap you with anyone else at this time. There is an empty room across the hall, not within the clan rooms, that you can use. Although it doesn’t have the same facilities that your current room has.”

“That doesn’t matter. It will be fine,” said Aronoke.

It was a small matter to move his stuff across to the new room. The isolation of the chamber made it easier to think of himself as being separate. It was the perfect opportunity to divorce himself from his clan-mates, at least in appearance. He must be strong, must not let himself be made miserable or angry by this self-imposed distance, because then the voice would have won. He had to be calm and resilient. He had to be a Jedi.

There is no emotion, there is peace.

It was difficult. There was an undercurrent of sadness that Aronoke found impossible to erase entirely. He could control it while he was meditating, but every time that Draken asked him to play a game, or any of the little kids were particularly forthcoming, he forced himself to be friendly but stand-offish and it came back. Draken seemed puzzled and hurt, and the little kids looked at him oddly like he had been replaced by someone who was not really him.

Just when he had felt he could really belong, Aronoke thought, something happened to force him apart again. Was that what it was always going to be like? Eternal isolation?

Nevertheless, Aronoke persevered in his self-imposed solitude for a couple of weeks. Buried himself in his lessons. Increased the amount of time he spent running and meditating and did a great deal of extra reading to pass the time. Walked down to the pool regularly to look at the water. It was difficult to occupy his mind with enough things to keep himself from feeling depressed, although all the meditation helped a lot. He felt he was getting on top of it most days.